David Letterman's retirement is gathering velocity. May 20th. Oh, my god. Is one of the five stages of grief Nostalgia? It's been flooding over me lately. When I was little, my dream was to be interviewed—about what, I don't know—by Johnny Carson. Then when he retired I set my sights on David Letterman. I can see I'm going to miss that one by a long shot too. But there was one person peripheral to my life who had the pleasure of performing on Letterman about twenty times in the 1980's, and his name was Brother Theodore and for one night, he was my babysitter.

Even by the lax standards of 1970's parenting, inviting Brother Theodore to babysit me and my sister was remarkable, bordering on insane.

My parents' act, "Jennifer and H." My mom was Jennifer.

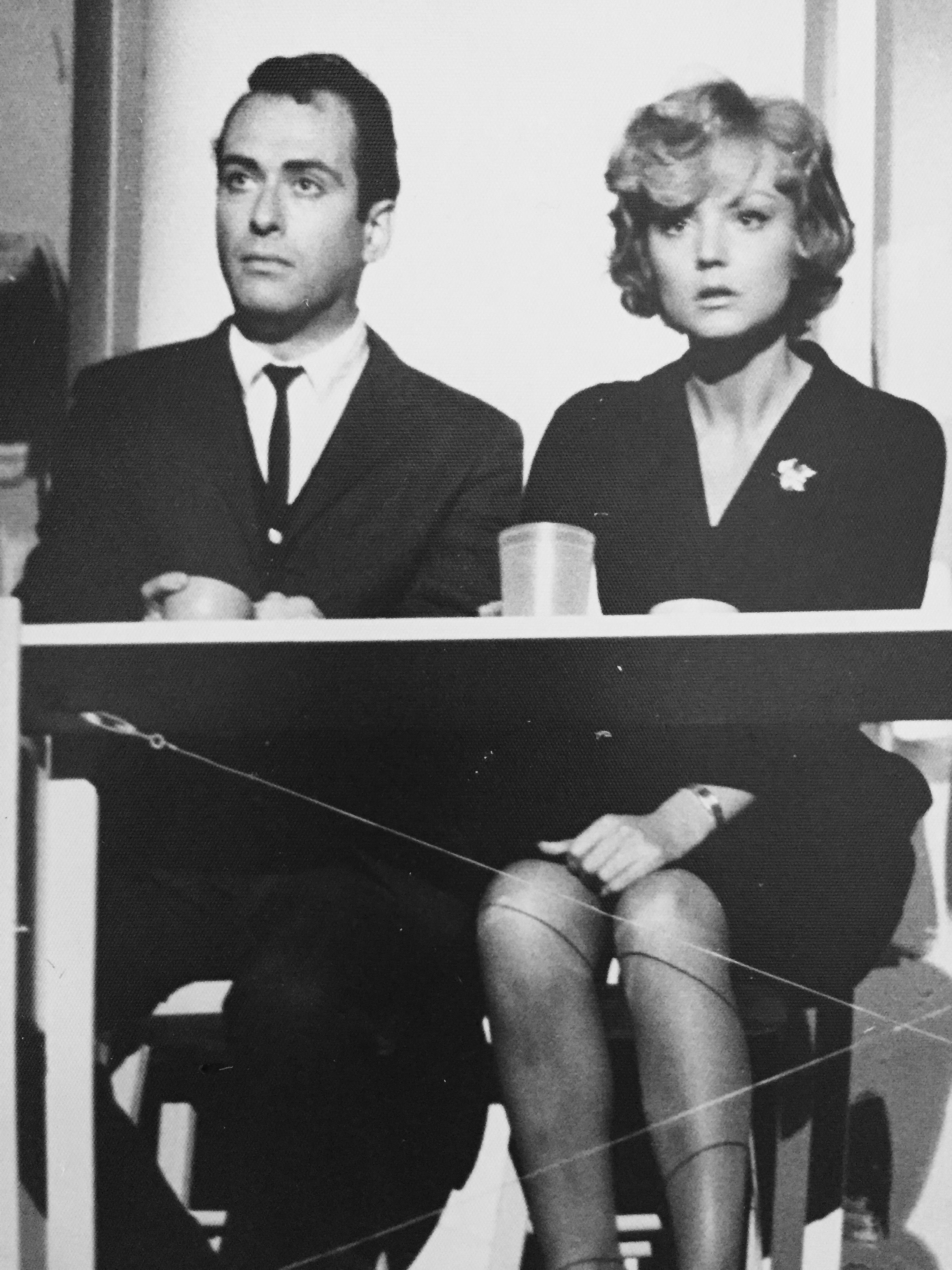

Brother Theodore, born Theodore Gottlieb, was a good friend of my dad and mom's from their nightclub days in New York City. My parents performed sketch comedy together in the 1960's in the vein (but maybe not quite the heart) of Nichols and May or Stiller and Meara. Everybody on that circuit was interconnected and so my father discovered and became a devotée of Theodore's midnight show in the East Village.

My father and Theodore had an immediate appreciation for each other. My dad even made a short film based on Brother Theodore's act. I put a link to it at the bottom of this post (I believe my Mom is the woman sitting on Theodore's lap because I recognize her English teeth). They both considered themselves to be intellectually superior (true), they were obsessed with word-play, chess, arcane knowledge and Orson Wells. They were also depressives with a somewhat bleak view on life. Excepting each other, they were used to being the smartest, wittiest person in the room and they weren't shy about it. My dad once proclaimed "I'm a better writer than Dostoevsky." Having not yet read Dostoevsky and at that point being completely in my father's thrall, I believed him.

Both Brother Theodore and my family lived on the Upper West Side, so he would stop by our apartment at least once or twice a week. My mom would make coffee and then the men would play chess. My dad was very good, excellent, in fact, but Theodore was a first-rate chess hustler so it wasn't really a fair fight. My dad would sweat, strain and curse under his breath so his children wouldn't hear, but of course we did. Theodore would keep a stream-of-consciousness play-by-play going to distract and fluster my dad and to entertain Herb's little girls. It worked. My dad would grit his teeth and stare so intently at the chessboard I thought it might go up in flames. Much of the gibberish was a hybrid of German, of which I understood virtually nothing—he called one of his most deadly chess moves "the fuboobounce"— but I knew it was funny and that my dad was trying desperately not to give Theodore the satisfaction of laughing, My sister's and my gigglings were Theodore's perfect audience. It egged him on to entertain and torture my dad even further.

For people who aren't familiar with Theodore's work, here's a bit of background. He was the voice of Gollum in the animated version of Lord of the Rings. But before that, Steve Allen, Merv Griffin and Tom Snyder were big fans. I think Merv Griffin may have been the first to call him "Brother" Theodore, but I'm not positive about that. After a series of professional setbacks, David Letterman took a shine to him and was single-handedly responsible for Theodore's career resurgence. He was one of Letterman's favorite regular weirdos, except both Letterman and Theodore were in on the joke. They had a vast appreciation for each other's sardonic intelligence. Theodore would rant and rave and Dave would play the straight man, but not really. Then Theodore would pretend to be enraged by Dave's irreverence, transporting him to greater heights of lunacy.

Theodore performed German Expressionist horror-humor monologues. He was an absurdist storyteller. He began his tales with quiet, courtly menace and then build to a demonic, bellowing climax of depravity. His face contorted, spit would fly out of his mouth and his deep-set eyes would pop out of his head—to me and my sister, literally. It was comedy of the grotesque. My father loved it, my mom less so and my sister and I, not one bit. A question still lingers in my mind why we were allowed to watch these performances at all.

One of Brother Theodore's favorite monologue subjects was his love of pre-pubescent girls. He seemed fascinated and repelled by their purity and innocence, like a Grand Guignol Lolita. And so, naturally, my parents chose this man to be one of our babysitters. I recently asked my mom what the thought process behind this decision had been and her embarrassed response was, "Well, I don't really know what was going through my mind. He offered and we accepted." Fair enough.

When my parents mentioned to my sister and me that Brother Theodore was coming to babysit, we froze in fear. Theodore wasn't exactly a beauty. His complexion was ashen colored and mutated to beet red at the climax of his performances. His lips were brown and freckled. His cheekbones looked like gashes on his face. He did have nice, thick silver hair —and my father envied him, not having very much himself— but he sported a strange bowl cut that didn't flatter his enormous spherical face. And I never wanted to get close enough to smell him.

My sister and especially I suffered from mild separation anxiety, but it was in full bloom that night. We clung to my mom and dad and begged them in whispers to stay. After prying us off and promising to not be home too late, they left. I watched the front door close and heard the elevator in the hallway slide and seal shut.

Thank god we had already had our baths and were in our nightdresses. Children can have very little actual knowledge about sex and still feel what it is innately. I knew enough to be scared. Theodore's aspect wasn't making me feel any more at ease. He rarely smiled and when he did, it was more of a grimace. His teeth were unsettlingly white, like the Wolf in Little Red Riding Hood.

And guess what? Nothing bad happened. Not at all. In fact, Theodore was kind, attentive, mild and a complete gentleman. We played Connect Four. We watched a little TV and ate the meal my mom had prepared for us before she went out.

He did tell us a gruesome bedtime story about how he used to have a twin brother who was a cauliflower head growing out of his neck. The talking cauliflower would taunt, tease and insult Theodore until he couldn't take it anymore. He unsheathed a sword he had hidden in his closet and sliced the cauliflower head off, wrapped it in muslin and buried it the ground. Sometimes, around this time of night, if he listened carefully, he could still hear it whisper dreadful things about him. My sister was in the top bunk of our bunk bed. I was on the bottom. Theodore perched on the edge of my bed as he told this story. We listened without saying a word. After the story he wished us goodnight, no hugs and, thank goodness, no kisses and left our room. I stared at the underside of my sister's bunk with my eyes wide open, just waiting out the night until my parents came home much, much later.

Cut to sixth grade, I was given an assignment to interview a friend or family member who had led an interesting life. I have no idea why my dad, who normally would have been more than happy to talk about himself, suggested I interview Theodore instead. I really didn't want to interview him. I wasn't scared of him anymore, I just found Theodore to be kind of pathetic.

He dated a string of very young women, most of whom were devoted fans from his midnight shows. He would describe some lovers' quarrel or another they'd had to my dad and complain about these girls' lack of sophistication, intelligence and compatibility with him. I wondered how such a smart man, a genius in fact, could be that dumb. At this point I didn't know much about human beings and relationships, apparently.

Mom in 1976

I sensed Theodore had an enormous crush on my mother. Unlike his young girls, my mom was substantial, well-read and rather aloof. And beautiful. Recently, my mom confirmed that he would come on to her frequently and officially asked to date her after my father died. She demurred. The fact that he could disrespect my father whom he loved and admired seemed very sad and self-destructive to me.

I was my typical diffident-with-a-tinge-of-sullenness, pre-teen self as I set up the tape recorder in front of Theodore. I dreaded talking to him. I started asking questions, none of which were good or insightful. He answered them politely and respectfully, but then he shifted the dynamic and began doing what he did best, telling me a story.

Theodore came from an aristocratic, German-Jewish family in Düsseldorf, Germany. Being Jewish was not of primary importance to his parents or to him. Wealth, status, culture and urbanity were. Theodore's mother was a beauty. His father was a highly successful publisher, but somehow balked at Theodore's desire to become an artist and was cruel and exacting. Theodore excelled at school and particularly at chess, which was well-suited to his analytical brain. He remembered his childhood being difficult because of his father, but in terms of wealth, luxury and standing, it was exceedingly comfortable.

Then came the Nazis. Theodore's family made no preparations for escape, thinking their wealth and influence would protect them from what had befallen lower class Jews. After all, The Gottliebs didn't really care about their Judaism. They were German first and foremost and part of the Nazi platform was restoring Germany to its rightful former glory. They thought they would get by relatively unscathed.

But they didn't. The Nazis stripped them of their paintings, burned the books in their library, took Theodore's mother's furs and gowns and gave them to officers' wives. The Gottliebs were reduced to the same dreadful state as the Jews they had formerly regarded with contempt. They were shipped off to Dachau, separated and most died or were slaughtered. Theodore told me one of the unspeakable horrors he witnessed was watching guard dogs tear apart men as their Nazi handlers laughed.

The only reason Theodore survived was because he signed over his family's multi-million dollar fortune. I'm still not sure why, after the Nazi's had his signed papers, they released him. That might have been a good time to interrupt him and ask questions, but I didn't. Theodore told me that he ran away to Switzerland, using his chess prowess to hustle for money. He scraped by until the Swiss authorities caught up with him and deported him to Austria, still under Nazi control. He was in real danger of being sent back to Concentration Camp, but then something extraordinary happened.

Albert Einstein, who had been one of his mother's lovers, used all his resources to smuggle Theodore out of Austria and bring him to California. Again, I should have asked him questions about this stunning information, but I remained speechless and useless.

Theodore found a job as a janitor at Stanford University, but became known for defeating professor after professor at chess, sometimes many at once. He moved to San Francisco, where he started performing, then to Los Angeles, where Orson Wells put the moves on Theodore's young wife. Then onto New York. The rest of the story I kind of already knew. However, Theodore never mentioned he had a son. My parents must have known, but I never knew he existed. I only found out about his son doing research for this piece. I can only assume the subject was painful to him.

I am stunned Theodore told me what he did. At twelve years old, I knew who Albert Einstein was, but I knew nothing of lovers, affairs and most of all, the horrors of that particular dark time in history. I had heard about the Holocaust. In fact, my dad's only attempts to teach me and my sister about our Jewish heritage were to pick up food from Zabar's at least twice a week, later demand that me and my sister date Jewish guys (we failed miserably at that) and lastly, that we never forget the Holocaust. I knew it was awful but somehow it didn't make much of an impact on my child brain.

What Theodore told me that day in his calm, quiet, cultured German accent was so incomprehensible, it made me dizzy. How could any person do this to another human being, let alone try to eliminate an entire race of people, my race, in a methodical, pseudo-scientific way? It was pure evil.

Like Theodore's family, I hardly considered myself Jewish. My mom was English-Irish Catholic. She had converted so her in-laws wouldn't die of broken hearts, their beloved boy marrying a shiksa! To her, being Jewish was a technicality. My dad was hardly more observant. He chose for me and my sister to go to a waspy, all-girl school on the Upper East Side. When he went for the school tour, he saw all the little girls lined up in their pinafores curtseying goodbye to their teacher and he must have thought, "This is as far away from Brooklyn as I'm going to get." The Preppy Handbook became my bible, teaching me how to operate in foreign surroundings and fly under the radar.

As Theodore talked, I realized that if I had been born during that time, the Nazis wouldn't have cared about my blonde hair or my lack of cultural identity. I would have been as Jewish as anyone else. I would have been lower than a rat. No amount of snobbery or seeming sophistication would have spared me the Gottlieb's tragedy.

I looked at Theodore differently after that school project. I understood his darkness, his gallows' humor, the wildness, mania and the ferocity of his stage presence. Comedy was his way of channeling and processing the horrors of what he had seen. He called what he performed "stand-up tragedy." His unwilling, intimate connection with death and evil forced him to confront the unthinkable. A line from his act: "I've gazed into the abyss and the abyss gazed into me, and neither of us liked what we saw." How perfect is that?

He showed me the identification tattoo on his arm. The Holocaust had actually happened, it happened to him. He was continuing to endure through his wit and his doggedness. For the first time, I didn't see him as terrifying or perverted or someone to pity. I saw him as incredibly brave. He was a survivor.

I wish I could find that interview and the paper I wrote for my class. We didn't receive grades in sixth grade, but I know did get an "Excellent." I remember Theodore being pleased.

The Midnight Cafe

Brother Theodore on Letterman. I love that he has no idea who Billy Joel is and couldn't be less impressed.