Okay, I’m not going to pretend that The Sentinel (1977) is one of my favorite horror movies. The Sentinel, which was released 45 years ago this week, is actually pretty bad. Some might argue that it’s terrible. But what I will say is that it’s definitely not boring. And when I was a kid, the commercial for it scared the shitout of me so it holds a special horrific fondness in my heart.

Written and directed by Michael Winner, The Sentinel is about a beautiful but troubled model, Alison (Cristina Raines), who moves into a massive brownstone apartment in Brooklyn Heights so she can have some independence from her controlling boyfriend, Michael (Chris Sarandon), as she’s deciding whether to marry him. The building itself is in perfect condition with grand paintings hanging in the hallways, and the gigantic apartment comes fully furnished and decorated like an upscale funeral parlor. While I would be completely creeped out by its design, Alison is charmed. Her chilly, busybody realtor, Ava Gardner, tells Alison the rent is $500. Alison says “Oh I’m afraid that’s a bit too much.” (!) So Gardner immediately lowers it to $400. Find me a New Yorker who wouldn’t live in a mausoleum for $400.

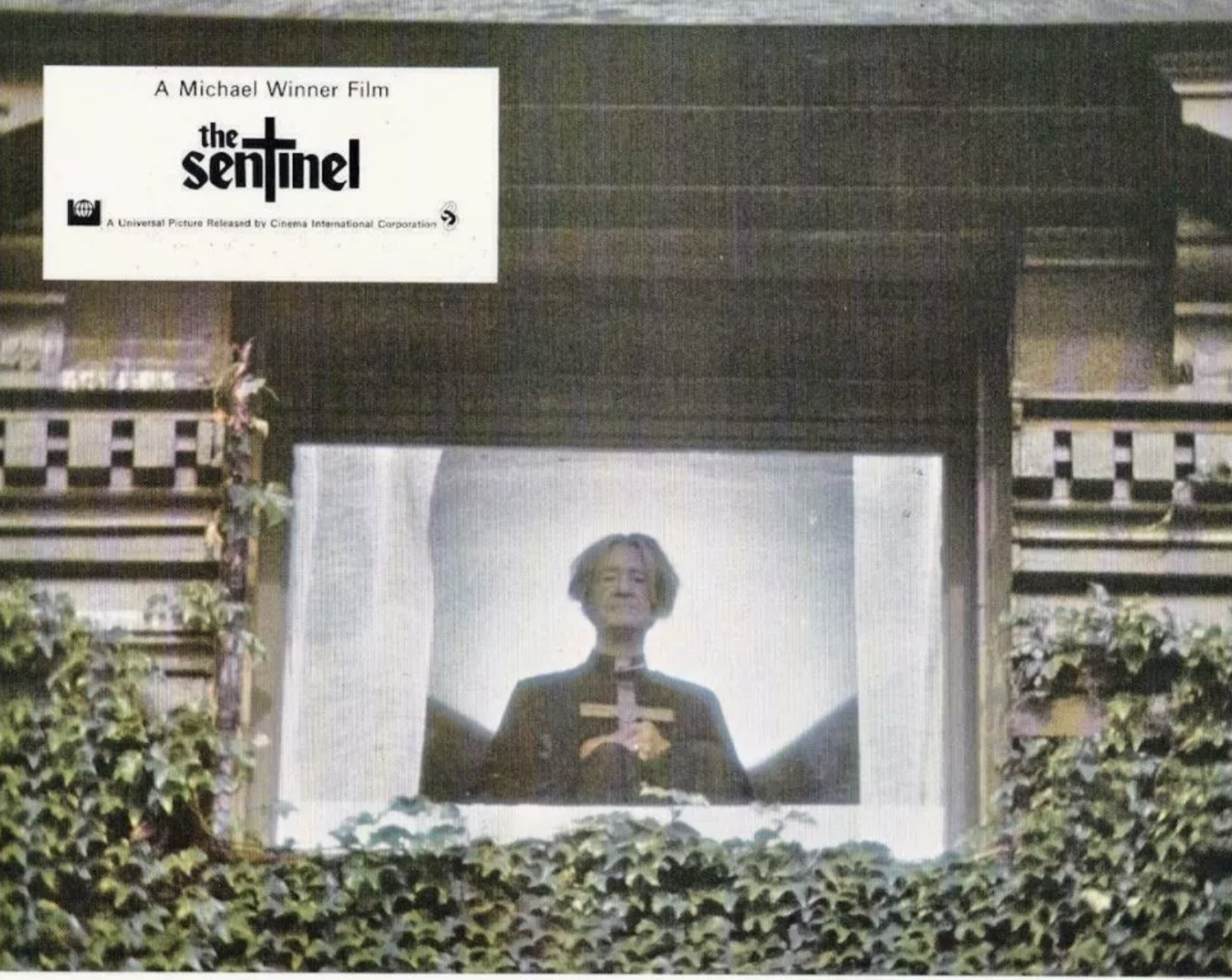

The only issue that gives Alison pause is that on the top floor there is a man in religious robes constantly staring out the window. “There’s someone staring at me from the fifth floor,” Alison says. “That’s Father Halliran,” Gardner explains. “He’s a priest. He’s kind of senile. He sits by the window. He’s blind.” Alison responds, “Blind? Well then what does he look at?” A very valid question, in my opinion.

Of course, according to the classic trope of horror movies, strange occurrences begin happening immediately after Alison moves in. She meets her eccentric—to say the least—neighbors (including Burgess Meredith and Sylvia Miles, among other cinematic luminaries) who are suffocatingly and relentlessly friendly and enthusiastic. She hears heavy footsteps walking above her at night. Lights flicker and chandeliers swing as she tries to sleep in her sexy lingerie. She experiences migraines, insomnia, and fainting spells, and it starts affecting her supermodel career. (Relatable.)

When Alison contacts the real estate broker, she tells her nobody has lived in the building save Alison and the blind priest for at least three years. (Dum, dum, DUMMM!) Too-long-story-short, this priest, (John Carradine) guards over the gates of Hell, the bizarre neighbors are ghosts of deceased homicidal maniacs who are also Satan’s minions (impressive multitasking), and Alison is a damsel in distress and is in for a devil of a time. As one might expect from a film by the director of Death Wish, New York City is a rough place and it ain’t for everyone.

It’s hard being a supermodel with a Devil of a migraine

There are a few things that make this truly demented movie remarkable. The lineup of famous 1970s faces is bonkers: Josê Ferrer, Martin Balsam, Arthur Kennedy, and Eli Wallach costar; Christopher Walken, Jerry Orbach, and Jeff Goldblum have bit parts. Uncredited actors include Charles Kimborough (“hospital doctor”), Richard Dreyfuss (“man on the street”), and Tom Berenger (“man at the end”). Notably, Beverly D’Angelo plays a mute reanimated murderer, but who dresses solely in red leotards and makes her presence known by simulating masturbation in front of Alison when Sylvia Miles invites her over for some neighborly tea (again, relatable).

Most remarkably, Michael Winner cast the other denizens of Hell with people who were sideshow performers (or from hospitals) who had significant physical deformities. According to Edgar Wright in “Trailers from Hell,” Winner instructed the crew to eat with them at lunch, “because they were ‘real people too,’ but he himself decided not to eat with them because he found them to be disgusting.” (If this essay can’t convince you to watch The Sentinel, available for rental on the VOD platform of your choice, Wright’s amused enthusiasm for this “rather unpleasant, in parts” film that “has gotta be seen to be believed” will likely do the trick.)

An aside: a personal nostalgic joy for me about this movie is that one of my father’s best friends, Hank Garrett, plays an unscrupulous PI hired by Michael to investigate Alison’s claims of evil, supernatural occurrences. Hank has had a fascinating life. His birth name was Henry Greenberg Cohen Sandler Weinblatt (can you believe he’s a fellow member of the Tribe?). In order to defend himself growing up in a tough Harlem neighborhood, he started lifting weights and actually won the 1958 Junior Olympic Powerlifting competition. Then he became a professional wrestler under the moniker “The Minnesota Farm Boy,” a natural name for a Jew from Harlem who most likely had never even stepped foot in the Midwest. He then segued to being a Borscht Belt comedian and then an actor in TV and films, most notably playing cops and heavies (sometimes hard to tell the difference) in Columbo, Kojak, Dragnet, Serpico, Death Wish, and Three Days of the Condor. While he played tough guys on screen, Hank was a delightful and upbeat presence whenever he came over to our apartment with his wife, Aggie. He kibitzed with my dad and they told stories and old Jewish jokes to each other, and he was absolutely wonderful with me and my sister. I had no idea he was in The Sentinel until I watched it last year. When I was little and not allowed to see his film work (and I would have been horribly bored if I had been), I wouldn’t have believed the sweet and funny guy cracking jokes and playing Connect Four with us at our dining table was also the murderer who tried to kill Robert Redford in an epic and brutal fight on film.

None of the actors in The Sentinel are at the top of their game and poor, beautiful Cristina Raines is in completely over her head. The cinematography is lackluster and sometimes even amateurish. The sound is subpar. There are a preponderance of orgies. The movie seems like a poor man’s version of The Exorcist meets Rosemary’s Baby. The script is laughably bad in parts. For example, Winner clearly tried to channel Bette Davis’s banter in All About Eve for Ava Gardner except the dialogue comes out as camp rather than witty. When Gardner asks Alison where she’s from and Alison says “Baltimore”—although her accent seems more like Baltimore by way of Tampa—Ava Gardner practically growls at her, “from Baltimore…how…nice.” If you are confused as to why being from Baltimore is of any significance to the realtor, you have something in common with me. And Winner makes Ava Gardner utter what I consider to be an instant classic: “I find New Yorkers have no sense for anything except sex and money.” Once again, as someone born and bred in New York City: relatable.

However, there is a grittiness and a daring that pays off. Christina Raines’s acting inability actually makes her more sympathetic and vulnerable. She genuinely looks confused and lost. Michael Winner’s utter lack of taste and decorum create some genuinely frightening scenes. The unrelenting Catholic guilt mixed with truly demonic sexual perversion is disorienting and nightmarish. The ’70s camera angles and zoom shots are also discombobulating and give us a glimpse into Alison’s personal hell, so to speak. Freaks must have been a seminal movie for Michael Winner, except he made no attempt to portray his own physically challenged cast sympathetically. They are meant to be seen as grotesque and evil. Imagine the outrage if this movie were made now.

It is vulgar and sadistic, but it is also effective. The final scenes are ghastly and terrifying. Maybe that’s what I sensed when I was little and was scared stiff by the commercial. It infected me even without seeing the movie itself. And even though it was poorly received when it premiered, The Sentinel has now become a cult classic, hence the adoration from auteurs like Edgar Wright.

Let’s not forget that this movie does something all great pictures do: it provides a little bit of wish fulfillment. Four hundred dollars a month for a floor-through brownstone apartment on Montague Street right off the Brooklyn Promenade is an absolute steal even if it is the gateway to Hell.