Here is maybe the best thing I have ever written:

The Wrong Side of 40

Last week, highly-regarded film critic Owen Gleiberman wrote about Renée Zellweger’s appearance, and how he thought she’d lost her essential self through plastic surgery. He hardly mentioned her magnificent range, vulnerability, or the legendary kindness that shines through her acting. Instead he chose to focus on the idea that, “In the case of Renée Zellweger, it may look to a great many people like something more than an elaborate makeup job has taken place, but we can’t say for sure.” So perhaps it shouldn’t be said at all.

I’m using “actress” in this piece for gender clarity even though I’m not a big fan of the word. To me, it implies a diminutive, lesser quality to a woman’s abilities compared to ”actor.” “Actress” seems to be more appropriate to an ingenue, which might be a tad insulting to an revered, seasoned woman like Dame Judi Dench.

Most of the time as an actress—especially while I’m working—I feel blessed to be in this profession. But my job is also tough for many reasons, and getting older is one of them. I am on the “wrong” side of forty, actually very close to Zellweger’s age.

Do I have lines around my eyes when I smile? Yes I do. Are my lips as full as they were when I was in high school? No they’re not. Is my body the same since I’ve had two big, healthy, happy boys. It isn’t. I live in Los Angeles where if you haven’t had your face and body “enhanced,” you begin to feel inadequate. I struggle all the time with these kinds of doubts.

I booked a job after I lost the baby weight from my first child. The head of the costume department called me up for my sizes and I proudly gave him my new weight, which was the lowest it had been since high school. I may have even been too thin. He replied, “Oh, so you’re normal sized. Good. That makes things easier for me.” I had practically starved myself for five weeks, but in film and TV this was considered “normal.”

I was really, really hungry while filming this

And last year my agent submitted me for a pilot in which the lead character was an obese woman. Every scene was her either having a hard time getting a dress over her head, getting winded or talking about how fat she was. I tried to explain to him that even by L.A. standards I wasn’t a good fit for the role. He consoled me by saying that if I did well in the room they might consider altering the character for me.

I laughed at this particular incident off because it was absurd, but being scrutinized constantly for my looks takes a toll. It’s hard for me to focus on a job I was hired to do when I’m worrying about how to stand so my tummy won’t bulge and my legs will look slimmer. It can even be self-destructive.

I feel like I look fine, yet I’m still ashamed to say how old I am. I don’t lie, but I avoid the subject because if I reveal my age, I’m worried I’ll be cast as a grandma (and not a young one). I should be proud. I’m comfortable in my skin, but because my profession takes place within an industry where youth is a calling card, it’s a challenge to stay grounded and honest. I’m afraid that if I admit my real age, I‘ll be judged not based on my abilities but by shallow perceptions of what unimaginative people think a forty-odd-year-old person should look and act like.

Maturity should be celebrated. Ideally, aging would benefit an artist professionally and personally. I’ve had more time to read, travel and meet people. I hope I’ve become wiser and more compassionate as a result. I understand human behavior more so that now when I’m playing different characters I don’t have to work as hard in my acting, like I did when I was younger, covering for my lack of knowledge.

If Renée Zellweger has had work done, it’s her own business. She has the right to do whatever she wants to herself. And perhaps part of the reason she may have wanted to change her appearance is because she’s been under intense scrutiny for her looks since she first appeared on screen.

When Jerry Maguire came out, I remember reading, ad nauseum, how unlikely a choice Zellweger was to play a Tom Cruise love interest, because of “her fetching ordinariness,” as Janet Maslin wrote in the New York Times. Her performance was breathtakingly sweet and painfully honest. Yet the big story was her “ordinariness.”

She doesn't look "ordinary" to me. Her sweetness and sincerity is luminous.

Looks can be an important tool for an actor. It’s undeniable. But it’s also unreasonable and dispiriting how often actresses get slammed (and even blamed) for their looks in a way male actors simply do not. Actresses’ lucky or “unlucky” genetics are tied to their self-worth and many times are prized more than their skill as artists.

Hollywood traffics in youth, so actresses tend to have a shorter shelf-life than their male counterparts. Harrison Ford is seventy-three and he’s still an action hero. I’m convinced Hollywood thinks actresses over fifty shouldn’t even have sex. Our earning potential decreases significantly because this business sees us as less desirable and marketable than men as we age. It’s no wonder some of us feel we have to take subtle or drastic measures to insure working as long and profitably as possible.

Post-Jerry Maguire, Renée Zellweger did something particularly daring for an actress. Something I’m not sure I’d have the guts to do: she gained thirty pounds to make her character believable in Bridget Jones's Diary. It was essential for the part: Bridget’s self-deprecation about her weight, her humor in battling through her awkwardness, her sense of being an outcast, a “singleton” in a sea of “smug marrieds” we're all features of her enormous charm. When she drunkenly lip-synced “All By Myself” after a breakup, alone in her tiny flat, I cried. And when she reunited with Colin Firth, who said he liked her just the way she was, I don’t think I was the only one who wanted to give Zellweger both a standing ovation and a hug.

Bridget Jones's Diary

Gwen Inhat, of the A.V. Club states it beautifully:

“But this imperfect heroine resonated with readers who also occasionally nestled beneath that low bar, taking two-and-a-half hours to pull together a simple outfit for the office, or frittering away an entire day supposedly spent working at home by looking at vacation brochures (followed by: “1:00 p.m.: Lunchtime! Finally a bit of a break.”) In a world where many chick-lit heroines and rom-com stars were often passed off as some sort of adorable type-A superwomen (like Jennifer Lopez’s super-organized Wedding Planner or Sophie Kinsella’s uber-ambitious Undomestic Goddess), the smoking, drinking, swearing Bridget Jones was funny, likable, and most of all, relatable. Many singletons of a similar ilk chose Bridget (or Fielding, more like) as their own personal heroine.”

It’s sad that I have to say it’s “brave” when an actress gains weight for a role. Did anyone in the Press criticize Robert DeNiro when he put on weight to play Jake LaMotta in Raging Bull? The gossip magazines breathlessly tallied every pound Zellweger gained or lost. It was a national fixation. She’s too fat. She’s too skinny. She has chipmunk cheeks! On and on and on. I’ll admit I was complicit in this ugly fascination too, which makes me feel ashamed. But at least I’m not a professional critic.

Google search for "Renée Zellweger weight gain"

How do you think this scrutiny makes an actress feel? Especially one possessing such openness and sensitivity? How did she block out all this toxicity? I’m guessing that no matter how much she tried, she couldn’t. It’s insidious and powerful. An actress can’t help but judge herself, to question her worth and to worry about her professional viability in the future. I have a hard time with my own efforts to be selectively sensitive. If Zellweger did have plastic surgery or fillers, she was probably trying to make herself feel better. To stave off the criticism and make her career last longer. To be proactive.

Whether he meant it or not, Gleiberman’s article was mean-spirited. He mused her changed appearance would affect his enjoyment of her performance, all from the Bridget Jones's Baby’s trailer. He’s a film critic, not a pageant judge. I hope Renée Zellweger didn’t read his piece, but I’m guessing she’s at least heard the gist of it. When I read it I couldn’t help but think about myself: if I became famous, would I be placed under the same cruel microscope?

When a respected, influential film critic starts reviewing an actress’ looks instead of the movie she's in, he becomes no better than an tabloid gossip columnist. It’s demeaning to his profession. I think Renée Zellweger and his readers both deserve better.

Bridget Jones's Baby

the many different stages of Prince

Prince

I hated Prince in high school.

I was a timid, unsure girl. Up until ninth grade I was skinny, wore thick glasses and I parted my freakishly long hair—my dad wouldn’t let me cut it—in the middle and let it fall down my back in one long braid. I attended an all-girl school whose student body was almost exclusively wealthy. Although my family was by no means poor, we were middle class which made me feel poor by comparison. I saw no hope of moving up any rungs of the ladder.

Do you see what I mean?

And then I defied my father by cutting my hair slowly, inch-by-inch, at each sleepover at my friends’ houses. And I started parting my hair on the side. And I discovered vintage clothing so I could rebrand myself as vaguely quirky and disguise the fact that I couldn’t afford Agnes B like my classmates. And most importantly, I switched to contact lenses.

Life changed. I sensed attitudes about me shift seismically. The cool girls felt more comfortable talking to me and invited me places. I started going to clubs and bars (carding people was extremely lax in 1980’s New York) and my new friends invited me to their country houses. It was a socially significant improvement.

But the most bewildering byproduct was that boys noticed me for the first time. Fear and maybe a little bit of anger clouded my happiness. Why now? I was the same person I’d always been, only the husk was different. As soon as they got to know me, these guys would see how profoundly awkward I was. If we kissed, they’d understand I didn’t belong, that I didn’t know anything, that other sophisticated, experienced girls would be more compelling, more aligned with their tastes.

I’d always loved acting and maybe one of the reasons I’m good was because I spent a lot of time practicing in my daily life during my teenage years. I’d already figured out my costume, now I just had to figure out how to look and feel like I belonged. I favored the British method: start from outside and work my way in. I hoped with much rehearsal this act would stick.

But I was deeply afraid. I thought everybody saw me as a good girl and I’d put so much effort into that role: I did my homework. I was neat. I was polite. I didn’t make waves. I followed rules. And to me, all these qualities didn’t jibe with sex. Somehow I got it in my mind that I couldn’t be good and also be sexual person, at least looking and feeling the way I did. You’d think going to a single-sex school would have built up my feminine self-esteem, but my high school was not that type of school. So I had these dark feelings I couldn’t parse because they didn’t match my exterior and I felt there was nowhere I could go. I talked to no one and was scared to go searching on my own.

I thought Prince was gross. Repulsive. Tiny, absurd, vulgar and a show-off. But truthfully, he frightened me. He wore sex graphically on his paisley sleeve. Like Bowie, he toyed with sexuality, but unlike Bowie, it wasn’t an intellectual exercise. It was dirty, explicit, flaunting and mocking. It dripped off him. “Darling Nikki” rubbed sex in my face. His music made me want to run away and hide.

In college I made a good friend named Gooey. No, I’m not making this up. Gooey was an honest-to-goodness eccentric and she took pity on me and held me under her wing. She lived in a one-room treehouse. She was from deep, rural North Carolina. She said without irony that her family was white-trash. In fact, they weren’t talking to her because she was dating a black man. She made her own clothes, she hardly drank and didn’t do drugs. She introduced me to her circle of smart and interesting friends, many of whom were musicians. She made me chicken and dumplings. I wrote her a recommendation when she applied to and was accepted into the Peace Corps. She was an extraordinary person.

Gooey probably explaining something to me

But perhaps what I associate most with Gooey was Prince. She played his music constantly. Pretty much exclusively and I was too much in awe of her to ask her to play anything else. So I sat in her treehouse and listened to the musician I couldn’t stand while she fed me dumplings.

Then one day I admitted that “Raspberry Beret” was pretty catchy. Come to think of it, “1999” was fun. “Purple Rain” was long and ornate, but the ending was mysterious and beautiful. Hmmm…maybe Prince wasn’t all that bad.

And then Gooey took me to the campus movie theater to see Purple Rain (of course I’d avoided seeing it when it first came out). Personally, I think Purple Rain is overblown and badly-acted (which doesn't stop me from watching it every time I'm flipping channels and happen to see it on TV). But those songs. Oh my god, those songs. I’d never seen any concert footage of Prince before and my mouth dropped to the floor. He played the guitar —and everything else—like an alien. And his dancing was unearthly too. For the first time, I understood Prince’s charisma. He was electric.

He was a virtuoso. He was a genius. Yes, he was strange but I finally realized that with his songs, he was both serious and in on the joke. And it dawned on me I was the one who had been humorless.

One of my most prized possessions

I’d been wrong. I didn’t hate Prince at all. In fact, I realized I was actually crazy about him. I’d been running away from him and he was waiting for me all along, quixotic smile on his face, to wise up and realize he was exactly what I’d needed.

Girl, come here and let me whisper a secret in your ear you already know.

Sex. It’s part of life. In fact without it, there’s no life at all. Sex can be dirty and complicated and confusing and twisted and beautiful, sometimes all at once. Oh, also sex is fun! Why cut myself off from that just because I was scared to see it?

I’m fairly agnostic and Prince clearly was not, but we both agree that sex is a divine gift and maybe the closest most of us can come to god. Ecstasy makes us both intensely aware of our bodies but also transports us outside ourselves. In the moment it’s impossible to think of anything else but that light. Prince may have seen purple, but I see blue. It’s the brief Rapture that allows us to return to Earth. And in the Church of Prince, it’s not a sin. It’s a duty. Fucking, for Prince, is a way of praying. Prince’s glorious music is the choir and his lyrics are the prayerbook.

The Ladder. Rave Un2 the Joy Fantastic. Take Me with U.

And while Prince was sincere, he also toyed with and mocked sexuality. He looked both sensual and ridiculous. It was like he was daring us to try to classify and compartmentalize him: “Am I black or white, am I straight or gay/Controversy”

The hair, the make-up, the clothes - they were costumes. They weren’t how he dressed privately. Prince was genuinely eccentric, but his eccentricity also had a purpose. With each album he had a new look and a new sound, but one message he repeated over and over was this: we are complicated people. No matter what sex we were born into, we are composites of both man and woman and sex lets us explore how we fit into the world.

Not sure very many people could get away with this and still be taken seriously besides Prince.

Pricilla wrote this wonderful piece about Prince.

In the song “If I Was Your Girlfriend,” Prince tackles all of this: If I was your girlfriend, would U tell me?

Would you let me see U naked then?

Would U let me give U a bath?

Would U let me tickle U so hard U’d laugh and laugh

And would U, would U let me kiss U there

U know down there where it counts

I’ll do it so good I swear I’ll drink every ounce

And then I’ll hold U tight and hold U long

And together we’ll stare into silence

And we’ll try 2 imagine what it looks like

Yeah, we’ll try to imagine what, what silence looks like

Despite his bravado, it’s clear that Prince loved women. As you can see from those lyrics, he seemed very generous. He wrote very few fuck-and-run songs. He’s bold without being macho or sexist. Most of the artists he mentored and wrote songs for were women and most of his songs were about them. He put women on a pedestal but he was also more than happy to knock that pedestal over so they could get down in the mud and have fun together. His opinions altered when he became a Jehovah’s Witness, but when I began loving him, this was the message he gave to me:

You can be a Madonna and a whore at the same time and there are no judgments.

Maybe I would have explored this anyway during my college years, but his music in my consciousness encouraged me not to define and limit myself to being a chaste, “good” girl. Good has nothing to do with denial. If I were truly good, I could search the deeper, darker parts of myself by myself or with other people and not compromise my essential nature in the least. This journey has gone in fits-and-starts and it’s not over yet, but despite never meeting him in person, Prince was one of the first to open my eyes to the notion that sex was crucial to my happiness and well-being.

There are so many reasons I love Prince other than his otherworldly talents. He was loyal to his fans, the people he worked with and his hometown. He could have lived anywhere but he chose to stay in Minneapolis and give back to the community. Despite his enormous fame and draw, he always played small, surprise venues to allow himself intimacy with his audience and to experiment musically. He honored and elevated the musicians who had influenced him not by copying them, but by filtering their music so that it was reminiscent but was its own transformed, unique creature. He also nurtured and promoted new artists. His battle with his record company was epic and brave. He was nobody’s slave. His music was for everybody, but he was always deeply committed to his community. He had a clever and sly sense of humor. For example, HE KICKED KIM KARDASHIAN OFF HIS STAGE BECAUSE SHE REFUSED TO DANCE!! How can anyone not love him for that?

I had hoped to see him perform. I thought there was plenty of time. As with Bowie, I stupidly believed, because he seemed superhuman, that Prince was immortal. He never lost his energy, his creativity or his edge. He almost looked the same as when he was nineteen and first appeared on American Bandstand. I can’t imagine anybody ever said “You know, it’s getting embarrassing. Prince should retire.” I never saw him live and I should have tried harder.

Perfect pop songs are almost impossible to write because they should be taken seriously but should also be catchy to reach a wide audience. My conservative guess is that Prince probably wrote at least 100 great pop songs (that I know of), appealing to people who liked not only that genre, but blues, soul, funk and rock n’ roll and music I can’t define. Black and white and all shades in between. “Money Don’t Matter 2 Night,” “Anotherloverholeinyohead,” “I could Never Take the Place of Your Man,” “I Wanna Be Your Lover,” etc. That’s insanity. There’s a vault in Paisley Park with thousands of Prince songs we’ve never heard. I’m overwhelmed by the thought of what gems are lying inside waiting to be loosed upon the world.

I’m crushed by Prince’s death. I can’t believe I feel this much sadness for someone I didn’t know in real life. I’m worried about what medical examiners will discover from his autopsy. I think he was in deep physical and psychic pain. Although I couldn’t hold Bowie in higher esteem, when he died I didn’t cry. I felt Prince’s death viscerally because he is partially responsible for teaching me how to live my life viscerally and with more passion. He sent a scared girl on her way with a gentle push to explore a dark, vast forest, like a benevolent version of the Wolf in Little Red Riding Hood. I’m sure I’m not alone in my feelings and I’ll keep him and his music alive in my heart for the rest of my life.

David Bowie

I didn’t think I’d write about David Bowie. There are so many people who are more devout and knowledgeable than I am. A few weeks ago I thought I’d have nothing to add to everyone's tsunami of grief.

But the night he died I couldn’t go to sleep. It was such a shock. True to form, Bowie kept his illness a secret. He’d released his latest album two days earlier to acclaim. On his sixty-ninth birthday. Of all rock star icons, he seemed immortal. He was unearthly and intangible. Like a mirage, never real to begin with.

I went on Twitter and listened to the people I follow and respect write one-hundred-forty-character tributes and prose-poems of admiration. I read old articles, I watched concert videos and songs my friends posted from YouTube. Twitter is wonderful at times like this. It was a late-night wake for a man whom almost everyone revered. I say "almost" to cover my ass, but I can’t imagine anyone who wouldn’t respect him. We all held invisible hands and shared thoughts, feelings and remembrances of him. It was quiet, sad and beautiful.

I texted my friend Christiana who had schooled me on everything Bowie when we were in high school. Even though it was 4am on the East Coast, I knew she’d be up and she was.

We reminisced. We watched part of a concert Bowie had performed for the firefighters and policemen who served during 9/11. He sat at a toy piano singing Simon and Garfunkel’s “America” while a montage of New York City scenes played behind him. There was no grandstanding, no self-indulgent emoting. It was apolitical, egoless and simple. He sang to say thank you to them. That was it. And because he was unsentimental the song was moving beyond belief.

That night Twitter engaged in the best kind of competition: “Isn’t this Bowie video great?” “Yeah! but watch this!” "Yes! That's amazing, but look at this." I heard “Station to Station” for the first time thanks to @PixelatedBoat. I downloaded it and danced in my kitchen at three in the morning. The next day I listened BLACKSTAR. I had to pull over to the side of the road when I heard “I Can’t Give Everything Away.” Knowing what we know now, the song is devastating and brave. It must have been heart-wrenching for him to write but also imperative.

I don’t pretend to understand all of David Bowie’s alchemy, but after many days thinking this is what I can articulate halfway. He was artificial but uncontrived. He was never out of fashion because he created fashion. His music was timeless. I shouldn’t even use the past tense because his songs will prove their own permanence. He was an approachable superhuman. Despite his stylized, aloof appearance he projected warmth in concert. Sometimes he was grotesque but he was always beautiful. He had an elementary sense of drama. Alien strangeness. One green eye, one brown.

I could never put my finger on him. As soon as I became comfortable with one of his personas, Bowie slipped away from me like mercury. He claimed his songs weren’t autobiographical and never would be, but once again he tricked us. BLACKSTAR is intimate and personal. It’s his own retrospective he allowed us to experience fully only after he died. Ironically it was his best selling album. I imagine Bowie Cheshire Cat-smiling.

He was a great actor and he was very funny. All his performances, dramatic or comedic, revealed an oblique sense of humor. His correspondences and interviews displayed his wry wit repeatedly. It seemed like he could do anything.

Bowie even handled aging well which most Pop Stars' egos won't allow. Bowie’s innate dignity, intelligence and elegance wouldn't permit him to act the fool. Unlike many other musicians who travel to India for three months then add a sitar and "exotic" backup singers to their next album to look worldly, Bowie seamlessly and respectfully incorporated different forms of music into his own sound. He supported and promoted other artists. He simplified his look as he got older without losing his style. He never became a parody of himself.

I’ve felt David Bowie’s death more acutely and enduringly than when most celebrities pass. It's obvious I’m not alone. We've lost someone unique and that's painful and hard. Thank god we have an embarrassment of riches from him to soften the blow. We will marvel at Bowie’s songs for as long as we live and we are lucky he came for a brief visit to our little planet.

The Force Awakens: One Woman's Conversion

After we found our seats in the movie theater, the woman sitting next to me and my two boys (five and eight) looked over at us and smiled. “Are your kids excited?” I told her yes, they were. “I think I was your older son’s age when I first saw Star Wars," she said. “I hope they love it as much as I did.”

I’m not a true Star Wars fan. I didn’t hate these movies—although I have completely forgotten The Phantom Menace, Attack of the Clones and Revenge of the Sith—I just never felt any particular passion for them. As I drove my boys to The Arclight theater in Sherman Oaks, I had to call my ex-husband so he could tell me the Cliff Notes. I appreciated the series’ impact, but the movies seemed overblown, ponderous, not to my taste—like an overdone steak with Bleu cheese.

I dismissed the The Force Awakens frenzy on Twitter. I didn’t want to spoil other people’s fun, but my general attitude was, “Oh, guys are so silly.” I'd exempted myself from the discussion and didn't really want to see it. But, along with sacrificing one’s body, sleep, sex-drive, independence and sanity, another thing a mother must endure is watching movies she’d have no desire to see if it weren’t for the sake her children.

But something happened when I entered the theater. It buzzed and vibrated with anticipation. There was a sense of belonging, of communion and strangely, of support. The excitement was contagious. At that moment it hit me: The Force Awakens was going to make me eat my hat even if I wasn’t wearing one.

The lights dimmed—no one really paid attention to the previews, just get to the main event, already—then faded to black. People started clapping and whooping. That unmistakable logo flashed up on the screen and the familiar, soaring music blasted through the speakers. Everyone burst into spontaneous applause, gasps and grateful laughter. I scanned the theater and I felt everyone’s bliss surrounding me, a quasi-religious experience. The hairs on my arm stood up. As I whispered the expository scroll to my five year old, I felt a slight catch in my throat. What the hell was going on? Why did I care about this movie all of a sudden?

Apparently, I'm not the only one who loved The Force Awakens.

I loved The Force Awakens. My boys and I went back again. Two times in one week. I feel as uncomfortable and guilty as when, as Yankees fan, I jumped full-force on the Mets bandwagon during the World Series. Yes, I am a Janey-come-lately. I understand your disdain. I acknowledge it, and I accept full responsibility.

Not only did I think The Force Awakens was great for a Star Wars movie, it was up there with Raiders of the Lost Ark, which I saw five times in the theater the summer it came out. Both movies shot me out of a cannon and never stopped moving. Both never sacrificed fully-rounded characters for action. The script was lean and quick. The filmmakers handled the exposition with grace and efficiency. The slower, more dialogue-heavy scenes only enhanced the speed and excitement of the action scenes that followed. I caught up on 30 years of backstory in under three minutes.

Chewbacca and Han Solo, back in the day.

The Force Awakens didn’t fall prey to the relentlessly solemn, self-important and dreary tone that seems to be the current fashion in other action movies. J. J. Abrams created a deft balance of light and dark—entirely appropriate considering its theme. And almost every character—not just Han Solo and Chewbacca—got to have his or her comedic moment in the sun, so to speak. The Force Awakens respected the reverence of its fans, while never taking itself too seriously, just like Raiders.

And speaking of Raiders: Harrison Ford. The audience cried out with pleasure when Han Solo and Chewbacca burst into the Millennium Falcon. I certainly surprised myself by laughing and clapping. For me, Harrison Ford always was the heart and soul of those movies, and he was back in true form. I don’t think I was alone in feeling I was reconnecting with an old friend, even more poignant because Han Solo actually was old this time. Curmudgeonly, irreverent, smart, sly and sarcastic; a good mask to cover up his sensitivity and vulnerability. That crooked, ironic smile. The perpetual loner and outsider. Perhaps, he connects to those of us who feel the same way in their own lives. In a world that often seems to run on incomprehensible rules (for example, the perpetual teenage state of being), he is a rebel who charts his own course and gets by on his intelligence, his wit and his ability to improvise. For his constant companion, he chooses an odd, loyal, hairy creature who speaks a language few people but he can understand: an imaginary friend come to life. Han Solo helps those of us who feel we might be a few steps out of rhythm with the rest of the planet at least pretend we are attractive and singular instead of just being alone. Again, I felt a catch in my throat.

Old pro's.

And when Han Solo, dying on the Starkiller Base’s vertiginous bridge, reached out and stroked the face of the son he lost to the Dark Side, my eyes welled up again. I am neither a father nor a son, but I do sympathize with that often difficult, conflicted relationship.

Fathers don’t carry a baby in their body for nine to ten months. Their feelings for their children often manifest later than mothers. When struggling with the concept of what it means to be a man, how does a father teach his son what he’s not sure he understands himself? He loves his son, but he’s competitive with him. Historically, fathers often left their sons for the majority of their childhood while they worked, but then were resentful when their sons wanted to distance themselves psychologically from them as well. I see with my own own boys how difficult it is to raise good men. It’s confusing. Signals are often crossed. Messages are mixed. Even if there is a backlash against the term “manly,” many still look down on men if they cry. (You only have to listen to last week’s scathing criticism of Obama when a few tears involuntarily ran down his cheek as he talked about first graders gunned down at Sandy Hook. This from the same people who have alternately accused him of being too remote and professorial on every other issue). I’ve seen for myself the stay-at-home fathers in my sons’ schools unconsciously ostracized by moms at social gatherings, as if we still don’t know what to make of them.

The struggle between fathers and sons is a dominant theme throughout the Star Wars series. The wish for connection and understanding verses the battle for control. A longing for each other, however perverse and fraught. Abandoned sons, unknown fathers. Love and death inextricably linked. Luke helped lead “the Rebellion” against his yet undiscovered father. The audience saw the conflict even reflected in the color of their costumes. As clear as black and white. Both fathers and sons are lost in space looking for the gravitational pull of the other.

Kylo Ren wore a mask to disguise the fact that secretly he was a scared boy. The filtered, altered voice hid any vocal nuance and hesitancy. It shielded the eyes that brimmed with tears. But when the mask came off, Kylo Ren was Ben again. A boy who missed his father but felt reconnecting was capitulating to weakness and failure. I looked over at my older son after Han Solo tumbled off that bridge and thought about the inevitable struggles he will face as he navigates manhood, and I felt my chest tighten.

I loved Rey, too. As a woman, I felt validated. She was the opposite of a helpless victim. She didn’t want to hold Finn’s hand when he tried to help her escape. She overpowered Kylo Ren’s Dark Force with her righteous one. She impressed Han Solo with her abilities. Leia noticed a younger, shimmering reminder of herself. Rey was a “princess” also, but not in the classic, passive, Rapunzel mold.

New favorites

Alone on Jakku, she learned how to make her way and survive in the desert wasteland. A weaker person would have perished from thirst, famine and maybe worst of all, loneliness. She hardly talked to a soul until BB-8 appeared, but she had a purpose which kept her company: to survive until her “family” came back for her. She carved a wall with chit-marks for each day that passed, like prisoners do in their jail cells to keep from going crazy. She taught herself how to scavenge. She taught herself how seemingly random objects she found fit together to make something useful to her.

In a series that has been dominated by male characters, it was refreshing to have Rey, like Finn, expand the diversity of the Star Wars “world.” I loved seeing Leia’s role deepen as well. C-3PO called her “Princess Leia,” but then immediately corrected himself:“General Leia.” It was a nice, subtle, but significant touch.

Then and now

In addition to Anakin/Luke and Han Solo/Ben relationships, The Force Awakens also touched on what happens to daughters when their fathers abandon them. When George Lucas ignored how Leia felt about being Darth Vader’s daughter, it grazed sexism. There was loneliness in Rey’s eyes as she waited for whomever she thinks would come rescue her from Jakku. Because she had spent almost all of her life alone in an uninhabitable world, she was stoic, serious and mature beyond her years. But she was still a young woman, full of feeling and longing as hard as she tried to hide it. When she met BB-8, Finn, Han Solo and Chewbacca (her non-related family) and left the limbo of Jakku, she learned to trust and rely on people other than herself. Even moments of happy surprise, relief and delight began to flash across her face.

Whether Luke is her real father or not, The Force Awakens tied them together intrinsically. I saw them begin to bridge their two isolated worlds—one formerly from the desert, one now atop a rocky island—in the final moment of the film. Rey held out the lightsaber to Luke. It’s the start of a connection, an understanding, an alliance and perhaps even a family. I can’t wait to see how their relationship develops in Episode VIII.

My five year old—perhaps too young for this movie—curled up and fell asleep on my lap. His warm little body lay across mine, his head pressed up against my neck. My older son sat two seats away from me, transfixed by the images on the screen, the blue light of the final battle flickered on his attentive face. It seemed to me, from the alternating cheers, laughter and rapt silence, that everyone watching The Force Awakens was enraptured. We were transported back in time, before life got complicated. This was a “long ago, far away” world both exotic and familiar. We were lost in the uncertain vastness of space, looking for our home. This was an adventure grounded in the search for family and identity based in real human emotions of fear, longing, sadness, love and regret. We were a bunch of strangers sitting in a shopping mall theater in Sherman Oaks, California, all travelling together on the same journey.

We clapped, we stayed until the Bad Robot tag. No one wanted to leave. Like a great production of Shakespeare, I didn’t have to understand every plot point or word. The writers, director, producers and actors did, and they made its meaning fluent. I left The Force Awakens feeling I had an experience that was bigger than myself, a universal one that the moviemakers passed on to my kids and all the kids in that theater, the way legendary tales have always been.

The Odeon

The Odeon is an iconic restaurant in TriBeCa. It was born in 1980 and even though I'm not great at math, I know this means The Odeon has been around for 35 years and it's still going strong -a rarity in New York City. It was on the cover of Bright Lights, Big City, the first (and I think the best) novel by Jay McInerney and was a favorite hangout of artists back when artists could afford to live in Manhattan. It is one of the few eating establishments whose name you can say to an NYC taxi driver and he or she will know exactly where to go. The Odeon has witnessed its neighborhood change and seen its share of comedy, drama and tragedy. In the late 90's I was fortunate enough to work there.

the basement

My family used to go to Thanksgiving at an intrepid friend's house in TriBeCa when I was a teenager. After dinner my sister and I would help him walk his Puli. In the 80's, the neighborhood looked as if fifteen people actually lived in the vast, industrial lofts. Except for West Broadway and Hudson, the streets were narrow and cobblestoned. It was quiet, eerie, desolate and romantic. Even though the hunting dog probably knew his route by heart and could guide us home if necessary, it was easy to become disoriented and lost. The only signpost that stood out as a beacon was the giant, red neon sign, "Odeon," and its subtitle on Duane Street, "Cafeteria," which is overly modest. Through its large windows partially obscured by horizontal wooden blinds, the restaurant was warm and inviting particularly compared to the Hopper-like loneliness outside.

Many restaurants have copied its Parisian bistro interior but none have done it as successfuly. The original co-owner, Keith McNally, was a visionary. Like the best designers, he knew a great set served its purpose, enhancing theatricality without stealing focus from the play. The bar was long and covered an entire side of the restaurant. It was always at least three patrons deep. Supposedly the cocktail "the Cosmopolitan" was invented there. I don't know if this is actually true, but it's a good rumor. The wood-panelled walls contrasted with the concrete floor; warmth coupled with severity, the old paired with the new. There was a pillar near two-tops one through five stocked with newspapers and magazines for patrons to read while they waited for their date or to keep them company as they ate alone. The pendant globe lights were low-lit and dreamlike, reflected in the mirrors all along the back wall. A person had the option to stare at themselves or not. The black and white tiled bathroom downstairs had seen its share of backstage drama but wouldn't tell a soul. The restaurant shimmered with sophistication and its hipness was aspirational. One day I would be worldly enough to go there for dinner, hopefully in the company of a handsome, mysterious man who perhaps was writing his Great Novel or was on a stopover while he traveled to Rome. Or Sting, a teenage obsession that utterly embarrasses me now.

I was hired as a hostess and showed up for training in what I thought was a nice outfit, but one look at the dining room and I realized I was in over my head. Even though they were in regulation black/white uniforms and bib aprons, the waitstaff's individual style shone through. Their languid boredom as the manager made announcements and Chef listed off the specials added to their allure. As some draped arms over each other or whispered conspiratorially, they looked almost post-coital. They were chic, sexy and exclusive. When I was introduced they regarded me with disinterest, like lions who were already sated from feasting on a gazelle's carcass.

After a short time working there I noticed the atmosphere changed dramatically over the course of a day. Lunch was pretty standard. The customers who came in tended to be people from the neighborhood who lived or worked there and business people or jury duty attendees on their hour break. The turnover was brisk and no-nonsense.

Early dinner were mostly families. At this time, TriBeCa wasn't a playground for the entitled. Those who chose to live there were usually creative, adventurous people. Architects, artists, writers and performers. You'd have to be an unusual type of banker or stock broker to consider buying an apartment in that neighborhood. Raising your child in New York City can produce selfish, myopic kids or preternaturally wise, sophisticated and interested ones. Most of the children who ate early-bird style at the Odeon were the latter. I credit their parents. Inevitably, if these parents were calm and sensible, so were their kids. I actually learned a lot watching these parents deal with their children in a thoughtful manner and I try to keep their example in my mind as I parent my own.

If it wasn't too busy, I liked to hold the babies for the parents so they could have a chance to eat unburdened. And I loved talking to the older kids, sometimes on the green bench outside. I was particularly close with one 6 year old, Isa. She had bright eyes and cocked her head at me like a sparrow when we talked. One time I asked Isa if she'd just gotten her ears pierced and she replied, "Zandy, I got them pieced a month ago! Where have you been?" Last summer as I was running along the Hudson River, a tall, young woman called out to me. Same face, same expression but on an adult. Isa was graduating college. She had exactly the same sweet, inquisitive spirit. I was thrilled she remembered me and unnerved by the rapid pace of time.

The night progressed like a piece of theatre. Sometimes a farce, sometimes melodrama and always compelling. I never got used to the eclecticism of the Odeon's clientele. As long as you could afford to pay the bill you were welcome there. Paint-splattered shorts and jeans were as accepted as tuxedos and evening gowns. People in fashion, photographers, publishers, writers, actors, models, financiers, singers, painters and everyone else in between came through those heavy glass doors.

The Odeon was a prime example of why people are drawn to New York City. The banquets were packed together and often tables would talk and laugh with each other having probably just met at the bar waiting endlessly for their table. No one minded being crammed into impossibly tight spaces. It enhanced the intimacy and energy of the restaurant. It was all motion, heat and light. And it was undeniably sexy. There were more than a few times I was sent to unlock a couple from a particularly warm, calisthenic embrace.

early evening, before things really kicked into high gear

Anyone who has spent a decent amount of time working in a restaurant knows the unspoken hierarchy. Chef is at the top. You do not piss off Chef. He or she has the power to make your life easy or turn it into a living hell. Luckily I got off on the right foot with the Odeon's. He saw a dutiful girl who wasn't looking to cause trouble and he always treated me well. He let me eat what he cooked for the rest of the kitchen- delicious, real Chinese food bearing no resemblance to General Tso's - told me to drink hot tea instead of iced when I had allergies and almost never raised his voice at me. Others Chef judged weren't so lucky. Customers become cranky when their food slows to halt out of the kitchen, as many waiters soon found out.

Under Chef came the general managers. The owner of the restaurant is technically at the top of the heap, but general managers who run the day-to-day operations were of equal or more importance. GM's seemed to get no credit when business was running smoothly and most of the grief when it wasn't. They also had to spend a large portion the day in a windowless room in the basement.

Our general manager was a man named Edward. He was a big man in stature and in personality. He was gruff, smart and sometimes caustic. A man of few words and pretty much all of them ironic. David Letterman was a semi-regular at the Odeon and that's who Edward most closely resembled. Big guys from the Mid-West who had to temper their sarcasm with slyness in order to fit in at home, eventually leaving for larger, freer cities where their edges were appreciated and were actually an asset. I was the complete opposite. If I came into his office, Edward would usually cut me off mid-sentence and I would wander back out discombobulated finishing it to myself. It became my goal to say something mildly intelligent or funny to try to win his approval. He seemed like a hard sell.

In the dining room, the bartenders were the leaders. They had separate rules from the waitstaff and were more like lone wolves. If they didn't like a customer or if he got too drunk and belligerent - I say "he" because in my experience this rarely happened with women - the bartender had license to cut them off and throw them out. This was always fun to watch. Like Page Six coming to life since many of the worst offenders were semi-well known. Bartenders could be surly, laconic and even rude and customers couldn't really do anything about it. Some of the customers even liked the abuse because, well, people are complicated. The men and the women who bartended at the Odeon were savvy and cynical. And they were generally gorgeous and sexy. Bartenders were the ones who got the most action and were mostly likely to break your heart.

Waiters were the next rung down, but not by much. They were all stunning in completely different ways. They were musicians, writers, actors, designers and a few were clearly models. Some didn't do much of anything, but who cared? They were great to look at. There was a different type of waiter for every type of customer who entered the Odeon. Some regulars came in expressly for them. It created a collegial, egalitarian atmosphere I've rarely seen in other restaurants. The waiters matched their customers in style, wit and substance. Many waited for their favorites and gravitated to the bar to have a drink or some other substance with them after their shifts were done.

The bar-backs and the bussers were, to a man, the most wonderful, kind and hardworking people at the Odeon. They received almost no recognition except a percentage of the waiters' tips. They were routinely ignored by customers and spoken to sharply by managers and staff alike. I marveled at their perseverance and even-tempered disposition. I couldn't do what they did and even if I could, I wouldn't be able to do it with such good grace.

One of the people at Odeon who stood out in particular was our m'aître d', a dashing Moroccan named Kahlid (a pseudonym). After I knew him a bit, I believed about 45% of what he told me but didn't mind because he was inimitable. For example, he said one of the most beautiful waitresses, also Moroccan, was his sister when actually she was one of the many women he was sleeping with. The complexity and chutzpah of all his lies was almost admirable. He was married to a poor, defeated-looking woman clearly for his green card, and they had a daughter whom he absently adored.

Kahlid was tall, handsome, impeccably dressed and masterful at his job. He'd generate tables out of thin air. He would have the busboys carry them up from the basement and create availability in minutes. He called every regular customer who was a women, "my princess," and every man "my brother" mostly because he couldn't remember their names, but they loved thinking they were singular. Everyone wanted attention and special treatment. He made everyone think he was theirs, but of course he belonged to no one. Kahlid was using them when they thought they were using him. It was one of the first times I saw "important" people act subserviently. I realized that people's attitude toward wanting food and drink was primordial and deeply personal, almost sexual. If they didn't get what they wanted, they reverted to a neediness bordering on rage. When they did, they were ecstatic and grateful. All they wanted was his momentary devotion. He told his customers with a Cheshire Cat smile that he'd have their table ready in ten minutes and they would happily wait at the packed bar for an hour.

Kahlid had a democratically mercenary view of the world. He never really listened to anything anyone said to him and he judged no one. The only thing he was interested in was the way a person could be of benefit to him. He was constantly scheming in one way or another. He could sell you some beautiful rugs, he could hook you up with a trip to Morocco, he knew someone who made suits or had access to premier seats to concerts or sporting events. Kahlid had his fingers in everything and relished the dirt. He hit on any mildly attractive woman who worked with him but wasn't offended if they didn't succumb to his charms. The first day I started working for him he tried with me too, but it was half-hearted as if he felt he had to go through the motions or I might think I was overlooked and abandoned. It was very nice of him to consider my feelings.

After I had been at the Odeon a a few months I became competent enough for him to consider leaving the floor for short periods of time, then longer. I was pretty much intimidated by everything but learned to pretend I wasn't. It was some of the best acting I've ever done. If you deal with snotty people calmly, reasonably with a hint of condescension as if they were unruly children, they generally snap back into shape.

I also got better at my job. I learned how to make sure everyone and everything at the Odeon flowed smoothly like a dance. You sit a waiter with the correct number of tables so he or she won't be slammed, so the orders will be properly timed with the kitchen, so the bussers will clear the tables to make sure the courses come out quickly but not so quickly that the customers feel rushed, so the check will be placed on the table at the appropriate moment, so that the customers without being aware are shuttled out of the dining room maybe migrating to the bar for an après dinner drink. Then you repeat this performance until the kitchen closes at midnight. Eventually regulars recognized me and even started to ask for me.

My competence was richly rewarded. Kahlid would sometimes leave for an hour or so. One night he said he was going across the street to Bar Odeon to teach them how to make Caesar salad dressing. Fifteen minutes after he had left the restaurant exploded. Kahlid's regulars were up in arms demanding his presence. I did the best I could and actually managed to placate and seat customers in the appropriate amount of time. I was fairly proud of myself. When the restaurant had calmed down I called over to Bar Odeon to find Kahlid. The waiter who answered the phone was confused: "Kahlid hasn't been here all night and Chef just sends over the same Ceasar salad dressing you have so why would he need to help us with ours?"

Kahlid blew in about ten minutes later, sniffing violently and said "What is this? What have you been doing to my restaurant?? You did it all wrong!"

I was and still am naïve about drugs. At the time I wondered how customers and waitstaff - we often sneaked sips during our shift - could drink so much for so long and stay seemingly sober, even energized. I only learned years later it had to do with coke and other substances I knew less about at the time. Coke had been offered to me several times when I was in high school during the heyday of 80's club life in New York City. I was terrified I would like it too much. It also seemed to exacerbate the worst individual qualities of the people doing it, and so I said no. Actually, I said I had done too much already so as not to look uncool and the people offering were so high they accepted my lie as truth. At any rate, the Odeon bathroom saw a lot of activity. Management must have been marginally aware of what was going on, but the restaurant was hopping night after night so they looked the other way.

Because he continued to leave me holding the reins at the Odeon while he went about his errands, I knew Kahlid actually respected my abilities. Eventually we became wary friends with each other. I was promoted to m'aître d' myself. Despite his shadiness, I had a soft spot for Kahlid. I knew his bravado barely covered his extreme insecurity. I saw the ambition that had allowed him to start as a busboy at the Odeon and work his way up the ladder to the top of the heap. He was an alley cat landing on his feet for the ninth time; a survivor. I admired him but I didn't want to get too close to him either. In his own particular way, he was an excellent teacher. Most of what I know about operating ably in a busy restaurant I learned from him.

in context

Eventually, the Odeon's magic started to wear off. The owner became more corporate. She made seemingly arbitrary decisions - no more tables seating six or more people, staff had to wear small earrings and roll down their sleeves and button the cuff so no tattoos were showing - ideas that in no way increased business but made her feel more in control. Kahlid left or was fired, it remained unclear. Many of the bigger personalities at the restaurant met the same fate.

The neighborhood also changed. More and more hedge-funders and celebrity-types bought property and turned the spare industrial lofts into opulent, showy pleasure domes. As befalls so many formerly funky neighborhoods, artists became victim to their own success; they were pioneers and had made the place livable and vibrant and safe. Because of their efforts, property values increased and then wealthier people arrived to poach what the original inhabitants had created. Many of them relocated to Brooklyn or Queens where rents were cheaper and where the bohemian spirit was more welcomed. Catering to this new, more entitled crowd amidst its own crisis of confidence contributed to the Odeon's edges softening, the atmosphere becoming more sedate and generic. Nighttime was still bustling but the Odeon lost a little of its sheen of danger and excitement. More cameras were installed, more rules were made. The staff felt stiff and nervous that they were going to be next on the chopping block.

Edward, who had unnerved me at the start of my Odeon tenure, ended up being the staff's biggest advocate and protector, certainly he was for me. Later, I found out I had been dangerously close to being fired, I'm not exactly sure for what. Maybe I was too vocal in staff meetings, maybe the owner felt I was too closely aligned with Kahlid or maybe something about my presence just rubbed her the wrong way. At any rate, Edward went to bat for me and I was spared. As probation for my unknown sins I was sent to Bar Odeon. At first I missed my Odeon friends (and the bartender I had a crush on). Even though it was right across West Broadway, I was mortified to be sent to what I considered as restaurant-Siberia

I soon realized that the owner had absolutely no interest in Bar Odeon and completely ignored it, which gave us the freedom to make it into exactly the place we wanted it to be. I tried to make the atmosphere less like a diner and more like a boîte. I dressed nicely and I asked the waiters to spiff up too. I brought in my mixed CD's (this was pre-iPod) and became the most inexperienced but eager-to-learn sommelier, choosing nice, fairly inexpensive wines to compliment Bar Odeon's solid bistro food.

Regulars from the Odeon started cheating with us. Even though our place was modest by comparison, the restaurant took on a bit of the ebullience and sophistication the Odeon had perfected before it had decided to become serious. It was a subversive pleasure to watch Bar Odeon start to succeed in spite of the owner's neglect and see customers and staff happy and busy.

Edward bought Bar Odeon from the Odeon's owner and renamed it Edward's. He is such a modest, unpretentious guy he felt uncomfortable with his name on the awning. But we convinced him it was the only choice. It's solid, straightforward and welcoming, just like him. It's a tribute to Edward that most of the original staff decided to take a chance and work for him instead of the Odeon. He had shown loyalty to us and we gladly returned the favor.

a matchbook from, Obeca Li, another restaurant around the corner from the Odeon, transformed into New York City's skyline at the time

Right before Edward bought his place, 9/11 happened. We were six blocks away from the World Trade Center. It was like a terrible, incomprehensible dream. We weaseled our way past the police barricades and back into the area four days after the disaster and helped clean out both restaurants and restore them to semi-working order. Then we opened and tried to go about business as usual, which was impossible because there was little to no business to be had. Only people from the neighborhood and emergency workers. No businessmen and certainly no revelers. None of us knew how to act or what to say to each other. What had happened was too enormous to comprehend. At the time it felt like the end of the world and in some ways it was. Nothing would be the same ever again. We did our best. We tried to be upbeat and casual in service to normality. We gave out free drinks and food to firefighters and policemen covered in what we later learned was poisonous dust and debris. We drank a lot. But it was hard to pretend to forget whenever you heard a siren or smelled the awful scent that pervaded the area; burnt plastic, metal and other things better not to imagine. We never got used to it, but we learned to adjust and feel grateful we were spared and had a place to go and something to do. We had taken those buildings for granted. I realized once they were gone that they had been a marker of where Manhattan ended and the river and ocean began, like the Odeon sign had been for me when I had been lost as a girl in TriBeCa.

I worked at Edwards for many years after that. It became my home away from home. It was my social life and the way I supported myself when I didn't have an acting job, which was a lot of the time. And whenever I did, Edward made sure I had my spot waiting for me when my acting gig was over. I established relationships and friendships with customers and staff that have lasted through the present day. I even worked there while I was pregnant with my first child because I liked the camaraderie so much. Everyone was especially nice to me then and many of my regulars insisted I sit down and relax with them while they ate and drank. I miss being there sometimes.

But working at the Odeon was a singular experience. Edward's felt like home. The Odeon never did. It felt like Oz. Maybe its allure was a sleight of hand, but I was full of wonder when I was hired there. I couldn't believe my good fortune to be actually living the fantasy that had played on a loop inside my teenage mind.

anchored

Brother Theodore

David Letterman's retirement is gathering velocity. May 20th. Oh, my god. Is one of the five stages of grief Nostalgia? It's been flooding over me lately. When I was little, my dream was to be interviewed—about what, I don't know—by Johnny Carson. Then when he retired I set my sights on David Letterman. I can see I'm going to miss that one by a long shot too. But there was one person peripheral to my life who had the pleasure of performing on Letterman about twenty times in the 1980's, and his name was Brother Theodore and for one night, he was my babysitter.

Even by the lax standards of 1970's parenting, inviting Brother Theodore to babysit me and my sister was remarkable, bordering on insane.

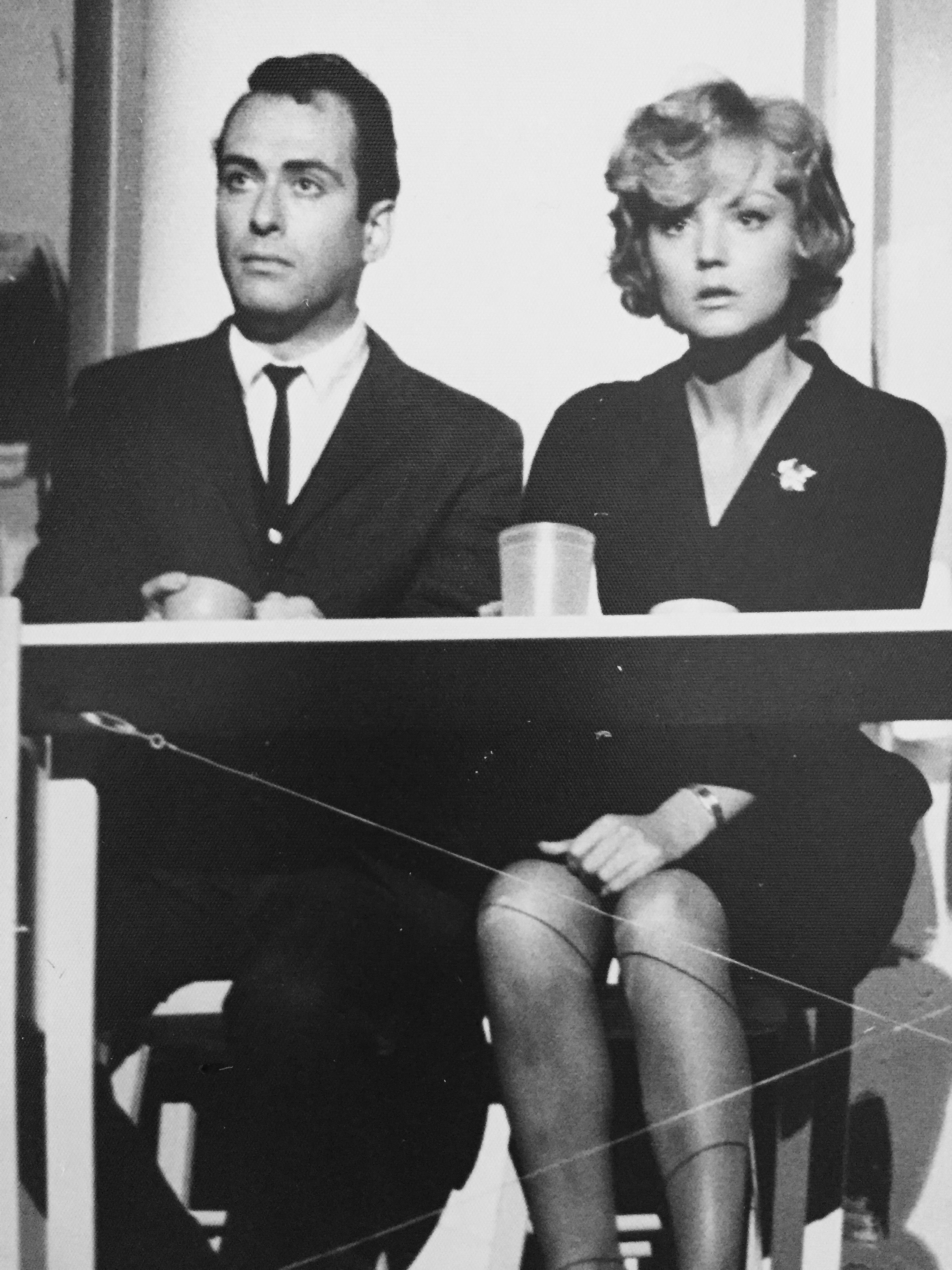

My parents' act, "Jennifer and H." My mom was Jennifer.

Brother Theodore, born Theodore Gottlieb, was a good friend of my dad and mom's from their nightclub days in New York City. My parents performed sketch comedy together in the 1960's in the vein (but maybe not quite the heart) of Nichols and May or Stiller and Meara. Everybody on that circuit was interconnected and so my father discovered and became a devotée of Theodore's midnight show in the East Village.

My father and Theodore had an immediate appreciation for each other. My dad even made a short film based on Brother Theodore's act. I put a link to it at the bottom of this post (I believe my Mom is the woman sitting on Theodore's lap because I recognize her English teeth). They both considered themselves to be intellectually superior (true), they were obsessed with word-play, chess, arcane knowledge and Orson Wells. They were also depressives with a somewhat bleak view on life. Excepting each other, they were used to being the smartest, wittiest person in the room and they weren't shy about it. My dad once proclaimed "I'm a better writer than Dostoevsky." Having not yet read Dostoevsky and at that point being completely in my father's thrall, I believed him.

Both Brother Theodore and my family lived on the Upper West Side, so he would stop by our apartment at least once or twice a week. My mom would make coffee and then the men would play chess. My dad was very good, excellent, in fact, but Theodore was a first-rate chess hustler so it wasn't really a fair fight. My dad would sweat, strain and curse under his breath so his children wouldn't hear, but of course we did. Theodore would keep a stream-of-consciousness play-by-play going to distract and fluster my dad and to entertain Herb's little girls. It worked. My dad would grit his teeth and stare so intently at the chessboard I thought it might go up in flames. Much of the gibberish was a hybrid of German, of which I understood virtually nothing—he called one of his most deadly chess moves "the fuboobounce"— but I knew it was funny and that my dad was trying desperately not to give Theodore the satisfaction of laughing, My sister's and my gigglings were Theodore's perfect audience. It egged him on to entertain and torture my dad even further.

For people who aren't familiar with Theodore's work, here's a bit of background. He was the voice of Gollum in the animated version of Lord of the Rings. But before that, Steve Allen, Merv Griffin and Tom Snyder were big fans. I think Merv Griffin may have been the first to call him "Brother" Theodore, but I'm not positive about that. After a series of professional setbacks, David Letterman took a shine to him and was single-handedly responsible for Theodore's career resurgence. He was one of Letterman's favorite regular weirdos, except both Letterman and Theodore were in on the joke. They had a vast appreciation for each other's sardonic intelligence. Theodore would rant and rave and Dave would play the straight man, but not really. Then Theodore would pretend to be enraged by Dave's irreverence, transporting him to greater heights of lunacy.

Theodore performed German Expressionist horror-humor monologues. He was an absurdist storyteller. He began his tales with quiet, courtly menace and then build to a demonic, bellowing climax of depravity. His face contorted, spit would fly out of his mouth and his deep-set eyes would pop out of his head—to me and my sister, literally. It was comedy of the grotesque. My father loved it, my mom less so and my sister and I, not one bit. A question still lingers in my mind why we were allowed to watch these performances at all.

One of Brother Theodore's favorite monologue subjects was his love of pre-pubescent girls. He seemed fascinated and repelled by their purity and innocence, like a Grand Guignol Lolita. And so, naturally, my parents chose this man to be one of our babysitters. I recently asked my mom what the thought process behind this decision had been and her embarrassed response was, "Well, I don't really know what was going through my mind. He offered and we accepted." Fair enough.

When my parents mentioned to my sister and me that Brother Theodore was coming to babysit, we froze in fear. Theodore wasn't exactly a beauty. His complexion was ashen colored and mutated to beet red at the climax of his performances. His lips were brown and freckled. His cheekbones looked like gashes on his face. He did have nice, thick silver hair —and my father envied him, not having very much himself— but he sported a strange bowl cut that didn't flatter his enormous spherical face. And I never wanted to get close enough to smell him.

My sister and especially I suffered from mild separation anxiety, but it was in full bloom that night. We clung to my mom and dad and begged them in whispers to stay. After prying us off and promising to not be home too late, they left. I watched the front door close and heard the elevator in the hallway slide and seal shut.

Thank god we had already had our baths and were in our nightdresses. Children can have very little actual knowledge about sex and still feel what it is innately. I knew enough to be scared. Theodore's aspect wasn't making me feel any more at ease. He rarely smiled and when he did, it was more of a grimace. His teeth were unsettlingly white, like the Wolf in Little Red Riding Hood.

And guess what? Nothing bad happened. Not at all. In fact, Theodore was kind, attentive, mild and a complete gentleman. We played Connect Four. We watched a little TV and ate the meal my mom had prepared for us before she went out.

He did tell us a gruesome bedtime story about how he used to have a twin brother who was a cauliflower head growing out of his neck. The talking cauliflower would taunt, tease and insult Theodore until he couldn't take it anymore. He unsheathed a sword he had hidden in his closet and sliced the cauliflower head off, wrapped it in muslin and buried it the ground. Sometimes, around this time of night, if he listened carefully, he could still hear it whisper dreadful things about him. My sister was in the top bunk of our bunk bed. I was on the bottom. Theodore perched on the edge of my bed as he told this story. We listened without saying a word. After the story he wished us goodnight, no hugs and, thank goodness, no kisses and left our room. I stared at the underside of my sister's bunk with my eyes wide open, just waiting out the night until my parents came home much, much later.

Cut to sixth grade, I was given an assignment to interview a friend or family member who had led an interesting life. I have no idea why my dad, who normally would have been more than happy to talk about himself, suggested I interview Theodore instead. I really didn't want to interview him. I wasn't scared of him anymore, I just found Theodore to be kind of pathetic.

He dated a string of very young women, most of whom were devoted fans from his midnight shows. He would describe some lovers' quarrel or another they'd had to my dad and complain about these girls' lack of sophistication, intelligence and compatibility with him. I wondered how such a smart man, a genius in fact, could be that dumb. At this point I didn't know much about human beings and relationships, apparently.

Mom in 1976

I sensed Theodore had an enormous crush on my mother. Unlike his young girls, my mom was substantial, well-read and rather aloof. And beautiful. Recently, my mom confirmed that he would come on to her frequently and officially asked to date her after my father died. She demurred. The fact that he could disrespect my father whom he loved and admired seemed very sad and self-destructive to me.

I was my typical diffident-with-a-tinge-of-sullenness, pre-teen self as I set up the tape recorder in front of Theodore. I dreaded talking to him. I started asking questions, none of which were good or insightful. He answered them politely and respectfully, but then he shifted the dynamic and began doing what he did best, telling me a story.

Theodore came from an aristocratic, German-Jewish family in Düsseldorf, Germany. Being Jewish was not of primary importance to his parents or to him. Wealth, status, culture and urbanity were. Theodore's mother was a beauty. His father was a highly successful publisher, but somehow balked at Theodore's desire to become an artist and was cruel and exacting. Theodore excelled at school and particularly at chess, which was well-suited to his analytical brain. He remembered his childhood being difficult because of his father, but in terms of wealth, luxury and standing, it was exceedingly comfortable.

Then came the Nazis. Theodore's family made no preparations for escape, thinking their wealth and influence would protect them from what had befallen lower class Jews. After all, The Gottliebs didn't really care about their Judaism. They were German first and foremost and part of the Nazi platform was restoring Germany to its rightful former glory. They thought they would get by relatively unscathed.

But they didn't. The Nazis stripped them of their paintings, burned the books in their library, took Theodore's mother's furs and gowns and gave them to officers' wives. The Gottliebs were reduced to the same dreadful state as the Jews they had formerly regarded with contempt. They were shipped off to Dachau, separated and most died or were slaughtered. Theodore told me one of the unspeakable horrors he witnessed was watching guard dogs tear apart men as their Nazi handlers laughed.

The only reason Theodore survived was because he signed over his family's multi-million dollar fortune. I'm still not sure why, after the Nazi's had his signed papers, they released him. That might have been a good time to interrupt him and ask questions, but I didn't. Theodore told me that he ran away to Switzerland, using his chess prowess to hustle for money. He scraped by until the Swiss authorities caught up with him and deported him to Austria, still under Nazi control. He was in real danger of being sent back to Concentration Camp, but then something extraordinary happened.

Albert Einstein, who had been one of his mother's lovers, used all his resources to smuggle Theodore out of Austria and bring him to California. Again, I should have asked him questions about this stunning information, but I remained speechless and useless.

Theodore found a job as a janitor at Stanford University, but became known for defeating professor after professor at chess, sometimes many at once. He moved to San Francisco, where he started performing, then to Los Angeles, where Orson Wells put the moves on Theodore's young wife. Then onto New York. The rest of the story I kind of already knew. However, Theodore never mentioned he had a son. My parents must have known, but I never knew he existed. I only found out about his son doing research for this piece. I can only assume the subject was painful to him.

I am stunned Theodore told me what he did. At twelve years old, I knew who Albert Einstein was, but I knew nothing of lovers, affairs and most of all, the horrors of that particular dark time in history. I had heard about the Holocaust. In fact, my dad's only attempts to teach me and my sister about our Jewish heritage were to pick up food from Zabar's at least twice a week, later demand that me and my sister date Jewish guys (we failed miserably at that) and lastly, that we never forget the Holocaust. I knew it was awful but somehow it didn't make much of an impact on my child brain.

What Theodore told me that day in his calm, quiet, cultured German accent was so incomprehensible, it made me dizzy. How could any person do this to another human being, let alone try to eliminate an entire race of people, my race, in a methodical, pseudo-scientific way? It was pure evil.

Like Theodore's family, I hardly considered myself Jewish. My mom was English-Irish Catholic. She had converted so her in-laws wouldn't die of broken hearts, their beloved boy marrying a shiksa! To her, being Jewish was a technicality. My dad was hardly more observant. He chose for me and my sister to go to a waspy, all-girl school on the Upper East Side. When he went for the school tour, he saw all the little girls lined up in their pinafores curtseying goodbye to their teacher and he must have thought, "This is as far away from Brooklyn as I'm going to get." The Preppy Handbook became my bible, teaching me how to operate in foreign surroundings and fly under the radar.

As Theodore talked, I realized that if I had been born during that time, the Nazis wouldn't have cared about my blonde hair or my lack of cultural identity. I would have been as Jewish as anyone else. I would have been lower than a rat. No amount of snobbery or seeming sophistication would have spared me the Gottlieb's tragedy.

I looked at Theodore differently after that school project. I understood his darkness, his gallows' humor, the wildness, mania and the ferocity of his stage presence. Comedy was his way of channeling and processing the horrors of what he had seen. He called what he performed "stand-up tragedy." His unwilling, intimate connection with death and evil forced him to confront the unthinkable. A line from his act: "I've gazed into the abyss and the abyss gazed into me, and neither of us liked what we saw." How perfect is that?

He showed me the identification tattoo on his arm. The Holocaust had actually happened, it happened to him. He was continuing to endure through his wit and his doggedness. For the first time, I didn't see him as terrifying or perverted or someone to pity. I saw him as incredibly brave. He was a survivor.

I wish I could find that interview and the paper I wrote for my class. We didn't receive grades in sixth grade, but I know did get an "Excellent." I remember Theodore being pleased.

The Midnight Cafe

Brother Theodore on Letterman. I love that he has no idea who Billy Joel is and couldn't be less impressed.

Amy Pascal and Jezebel

I haven’t been able to let go of my disgust after reading Natasha Vargas-Cooper’s poisonous Jezebel takedown of Amy Pascal. The continually-unfolding Sony hacking scandal revealed Pascal’s highly intimate Amazon purchases in addition to emails about her diet, all gleefully and ghoulishly recounted in Vargas-Cooper’s piece. On one hand, I’m angry with myself for consuming that toxicity and directing any more attention to it. On the other hand, I’m still shaken that a woman could do that kind of hatchet job on another woman. It seems like a double betrayal; one of privacy and one of humanity.

We may differ in our opinions about Amy Pascal. I personally hold no animosity toward her, but then again, I’m white. By all accounts she was a champion of projects that had artistic merit, was genuinely friendly to actors, creatives and executives and was one of the few women in Hollywood holding a position of prominence and power, which is no small feat. We need more people like her in this business, I assure you.

She did say some indelicate things. That may be too mild a descriptor. Okay, some of what she expressed in what she thought were private conversations was uncomfortably close to racism. However, I noticed that Scott Rudin, the person with whom she was communicating, didn’t get half as much flack for his portion of their conversations, which were equally if not more inflammatory. Maybe it’s because he has a reputation for brashness. That’s possible. My hunch, though is that it’s because he is a man, and men who are powerful are kind of expected to talk that way. Most of us love Glengarry Glen Ross. I certainly do.

As progressive as we like to think we are, women who are bold and decisive and strong are still perceived as threats. Not just in the Entertainment Business. Everywhere. Hillary Clinton certainly knows this. You don’t even have to be in a position of power. I have less than 2000 followers on Twitter and I’ve been called a cunt for a political opinion I posted. You probably don’t know me, but I’m one of the least assertive people in the Greater Los Angeles Area. Despite this, I’d obviously struck a nerve: How dare she express an opinion? Don’t women know that they are nothing more than a face, a body and a vagina, preferably hairless? To be honest, it didn’t shock me as much you’d think. This was the evaluation of a knuckle-dragger, someone who forgot that he actually came out into the world via the epithet he was using for me. Blocking people on Twitter is really easy.

The most shocking aspect of the Jezebel article for me was it was written by a woman. How could she do this? I assume Vargas-Cooper intended this to be a humor piece, but it read as if she was the chapter head of the Mean Girls’ Society of America (MGSofA). I don’t want to go into the specifics of Amy Pascal’s purchases, but I can’t imagine the humiliation of having them displayed in print for anyone and everyone to see. For me, it would be exactly like a recurring nightmare where you are in a crowd of people, you are suddenly completely naked and you’re desperately trying to cover up. It's inconceivable a woman wouldn’t know what damage this kind of information could do to the woman she was writing about.

Yesterday, I was searching my mind trying to think what could have motivated Cooper-Vargas to write this trash. I understand it’s an ugly side of human nature that we love to put certain people up on pedestals only to topple them over when we feel they’ve gotten too high. But I think there is something else at play that as a woman I find quite disturbing: whether it’s cultural or instinctual, women are taught to distrust and sometimes even despise one another.

It starts early. I have seen it in my children’s classrooms. And I realize I’m speaking in generalities, but when there is conflict between boys, they tend to knock each other down, cry and then get right back up and start to play again. However, between girls, it’s more complicated. They exclude and they whisper and they try to hurt. Unchecked, this kind of behavior can become even more toxic in High School. I went to an all-girl school. Believe me, I know.

I see the same kind of behavior at play in Cooper-Vargas’ post. It’s as if she is expressing the very feeling that women can’t tolerate when certain men express it: “Lady, you can’t have it all. You can be powerful or you can be attractive, but you can’t be both. If you try, then I will mock you and tear you down until you’re no longer a Superwoman, but a sad, grasping female who’s just longing to be pretty for a man." It’s not only disgusting, it’s heartbreaking. And it's sexist.